Meet the Staff: Ramon Jackson

After completing her basic training in the Army at Fort Jackson and briefly serving in Korea, my mother eventually landed in Fort Carson, Colorado. I was born on July 29, 1982, and spent much of my childhood alternating between Colorado Springs and Atlanta, Georgia. Prior to the start of my senior year of high school, we left Colorado for Atlanta one last time. Upon graduation, I attended The College of Charleston and earned B.A. and M.A. degrees in History in 2004 and 2007. After a series of peaks and valleys, I plan to complete my dissertation and earn my PhD from the University of South Carolina this fall. My dissertation entitled “Leaders in the Making: Higher Education, Student Activism and the Black Freedom Struggle in South Carolina,” is a series of case studies highlighting the role of African American college students as both student protesters and civil rights activists during the Long Civil Rights Movement.

As my Facebook biography says, I probably can be found “making history in your city.” Over the past decade, I have been privileged to assist with a several projects across our state including a campaign to commemorate the history of the 1955 Cannon Street YMCA All-Stars, served as co-historian with the Columbia SC 63: Our Story Matters civil rights initiative, and worked as a consultant on a major civil rights exhibit with Greenville’s Upcountry History Museum. None of this would have been possible without the patience and support of my wife, Dr. Joynelle Jackson, and the newest addition to our family, Leiana, who turns one in September. They are my sunshine.

What do you do as the African American Heritage Coordinator?

My role is to serve as the liaison between the South Carolina African American Heritage Commission (SCAAHC) and the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO). Among my duties are to develop and implement educational programs and special events including lectures, classroom engagements, and public meetings. I also assist communities in identifying and planning for the preservation, maintenance, and interpretation of African American historic sites and properties. Moreover, I also coordinate the SCAAHC’s social media campaign (@SCAAHC1993 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram), where I regularly promote SCAAHC programs, events, and publications such as The Green Book of South Carolina: A Travel Guide to South Carolina African American Cultural Sites, the Commission’s outstanding mobile travel guide to African American historical and cultural sites in South Carolina. This mobile guide features nearly 400 historic sites, museums, cemeteries, and cultural attractions for diverse audiences, allowing visitors to create customized itineraries for vacations, family reunions, field trips, walking tours, and other excursions. While initially created to spur cultural tourism across the state, we have found that teachers and students have greatly benefited from the historical narratives offered on the website. We are planning to add a section for educators complete with lesson plans and thematic historical tours.

Why did the Commission name the website The Green Book of South Carolina? The name is a homage to the original Negro Traveler’s Green Book, a segregation-era travel guide for African American tourists. First published in 1936 by New York postal worker and entrepreneur Victor Hugo Green, the guide was created to provide Black travelers with vital information to avoid the dangers, difficulties and embarrassments resulting from southern Jim Crow and de facto segregation in other sections of the country. With the aid of a cadre of informants—many of whom were Black postal workers—Green and his small but dedicated staff began to list segregated businesses nationwide beginning in 1938. Roughly 200 Black-owned businesses and other institutions in South Carolina were listed between this date and the final edition printed in the mid-1960s.

As part of my efforts to update our website, I decided to conduct a statewide survey of extant Green Book sites to determine how many, if any, of these buildings can be preserved and to document the history of former proprietors and their families. At present, we have learned that there is at least one extant building remaining in 8 of 20 South Carolina cities listed in the original Green Book. Multiple buildings remain standing in three cities—Columbia, Charleston, and Cheraw. We have also been fortunate to connect with several former proprietors and close relatives who have willingly shared stories that we plan to feature in a forthcoming “Historic Green Book Tour” on the Green Book website and other public programs. These businesses were important not only because they served as sanctuaries for Black travelers but also because they were sites of Black female self-determination, entrepreneurship and civil rights activism. Preservation of these spaces can also help us learn more about Jim Crow, civil rights, and the racial politics of urban renewal in our state. We’re just scratching the surface of what is possible. I’m excited about the future of this project and invite your readers to join our efforts!

Why did you want to work in the field of history?

None of this was planned. [Laughs] When I was in seventh grade, my dad often forced me to read U.S. history textbooks as a “break” from my seemingly never-ending quest to save the Mushroom Kingdom from King Koopa. From high school through my first year of college, I excelled in reading, writing and history courses but never thought of this as a possible career path. Former CofC professor and Avery Center director Dr. Marvin Dulaney, who was my advisor, encouraged me to apply for a docent position at Avery. As part of my duties, I gave public tours, processed collections, assisted with public programs, and read nearly every book in the Avery Gift Shop. Dr. Dulaney eventually convinced me to major in History and served as the chair on my thesis committee. I researched and wrote a history of the Cannon Street YMCA All Stars, an all-Black youth baseball team that was denied the opportunity to play in the 1955 Little League World Series due to segregation. Over the next decade, I worked with team historian Gus Holt and others to commemorate this history in a variety of ways including the placement of a historical marker at Charleston’s Harmon Field.

Two USC professors, Dr. Bobby Donaldson and Dr. Valinda Littlefield, guided me through graduate school. Over the past decade, I have been privileged to assist their efforts to help Black communities document and preserve their histories while also organizing community leaders, activists, alumni groups and other stakeholders to restore and preserve African American historic sites. These experiences have taught me that we don’t simply study history to equip ourselves to speak truth to power but we do this to empower others to speak their truth.

During my tenure with Columbia SC 63, Dr. Donaldson and I were able to recover the history of civil rights struggle in Columbia and South Carolina. Our team developed a series of exhibits, public programs, tours and other events that sparked conversations and generated renewed interest in the story of the movement and its participants. I’m always thrilled to see young children and their parents reading the wayside markers that were erected on on Main Street. Moreover, I’m glad to see that the work continues. Evidence of this is the Justice for All exhibit that was on display at the Ernest F. Hollings Library in 2019. Be sure to view the digital exhibit that is still available through University of South Carolina Libraries Digital Collections.

Do you have a favorite collection or document from our collections and why is it your favorite?

At present, I don’t have a favorite document or collection. I can, however, highlight a property that I think best represents the importance of our ongoing Green Book survey. SHPO and the SCAAHC have had tremendous success in documenting, interpreting, and preserving African American historic sites over the past three decades. Since 1993, the number of historical markers erected at African American historic sites has increased from 25 to nearly 400! This year alone, roughly half of the historical markers erected have commemorated our state’s African American heritage. Numerous African American historic sites have also been listed on the National Register for Historic Places. No other state boasts such a record.

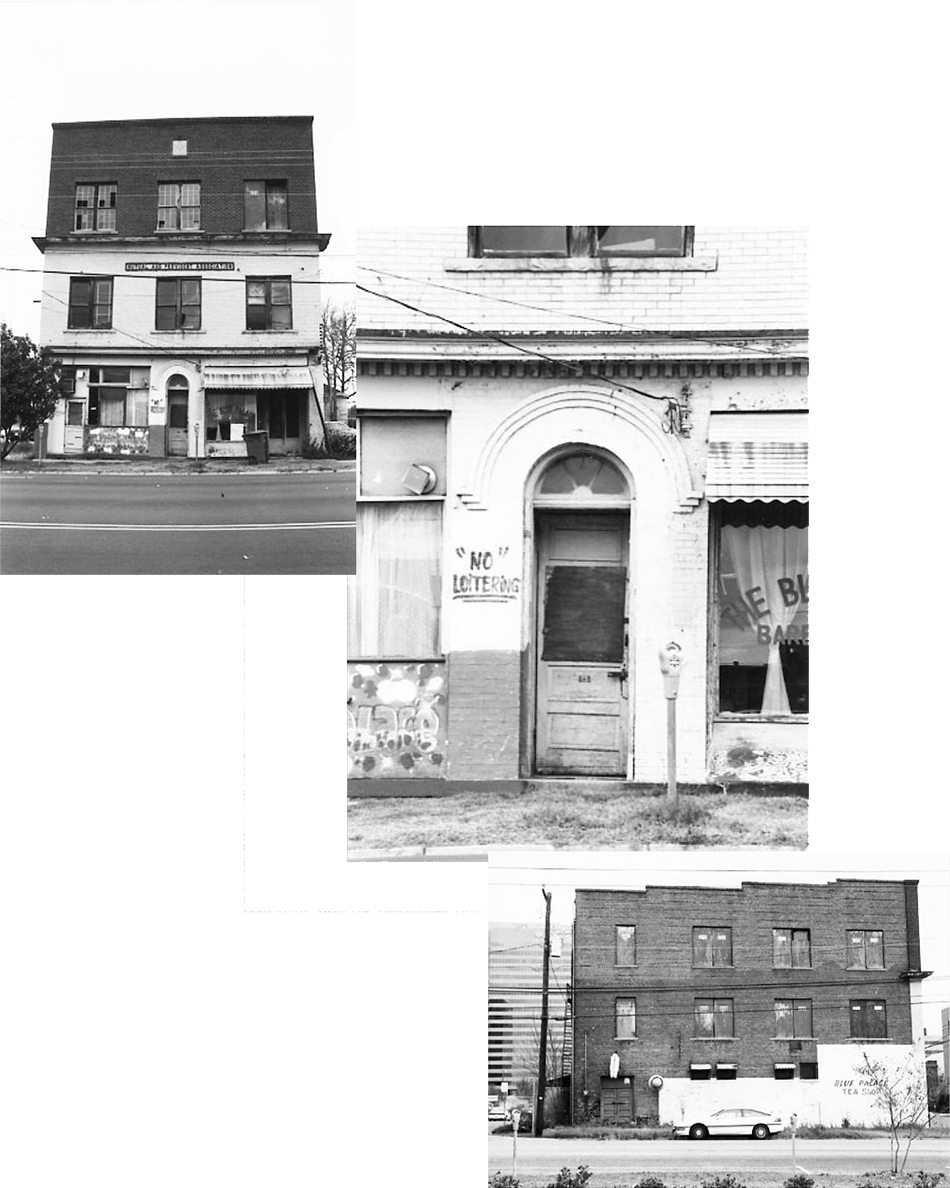

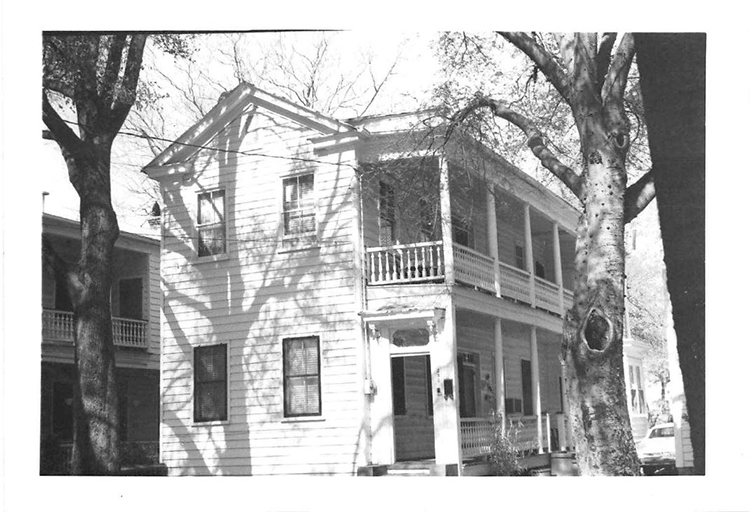

There is always more to learn about historic sites that we have long considered fully documented. The North Carolina Mutual Life Building located on 1001-1003 Washington Street in Columbia (NRHP #S10817740103) is an example. Built in 1909, this commercial building sits in the heart of what was once a thriving Black business district in the segregated capital city. It was home to the local branch of the North Carolina Mutual and Provident Association, the largest Black owned life insurance company in America. The company used three of the offices and rented the other spaces to local businessmen. Though it sold the building in 1920, North Carolina Mutual continued to maintain an office here until the mid-1930s.

The existing National Register nomination provides little information about the history of the building beyond this date. It was listed in the National Register in January 1995 and several images are featured in our SCPHR database. A second glance at the images reveals that this building was once home to the Blue Palace Tea Shoppe, a Black owned restaurant listed in the original Negro Travelers’ Green Book from 1948-1955. Owned and operated by C.C. Williams, the restaurant was likely open as early as January 1943. Williams lured customers with promises of delicious, home cooked fried fish and chicken dinners in advertisements featured in The Lighthouse and Informer. The civic minded proprietor promised “Cleanliness, Courtesy, Quality” to visitors for the 1946 SNYC Southern Youth Legislature and commended the organization for their work in creating better citizens for the Columbia community. There are many vacant buildings with similar stories. Our survey of extant Green Book sites provides us with an important opportunity to revise our records and capture these forgotten narratives before it is too late.

What is your favorite part of the job?

First, I want to thank everyone at SCDAH for making me feel welcome. I’ve enjoyed learning about the various SHPO programs and assisting our citizens with their efforts to commemorate African American history. The best part of the job is when I have the chance to leave the Archives and take photographs of extant Green Book sites in Columbia or other parts of the state. Since arriving at the Archives in February, I’ve worked in places as diverse as downtown Charleston, scenic Penn Center in Beaufort, and distant Sandy Island. I’m blessed to have the opportunity to travel, meet new people, and document stories about the past.

What is your favorite historical time period?

Lately, I have become enamored with the Long Reconstruction era (1876-1915). Close study of this period informs us about the tenuous nature of freedom after the Civil War and reveals the power of our stories and myths as foundations for the construction of racially inclusive, universally beneficial societies or segregationist regimes. The gradual transition from Reconstruction to Jim Crow was justified, in part, by the stories Americans told themselves about the purpose and meaning of the Civil War and the tremendous social and political changes that resulted. The Archives’ current exhibit South Carolina’s Reconstruction: Restoration, Revolution, Reaction reveals a great deal about white and Black South Carolinians’ competing visions of freedom and how the emancipationist vision of the war was suppressed in favor of the myth of the “Lost Cause,” a white supremacist narrative that privileged national reunion over racial justice. The 1868 and 1895 South Carolina Constitutions crystalized these competing visions and, in many respects, reveal just how quickly a society can descend from idealism to despotism. By the turn of the 20th century, African American churches, schools, and universities were essentially the only spaces where the emancipationist history of the war and truth about Reconstruction—epitomized by DuBois’ seminal text Black Reconstruction—were taught. These narratives inspired many young activists to march, picket, and protest for civil rights in later decades. The Dunning School or “Lost Cause” narrative about the failures of Reconstruction, however, was institutionalized in ways that we still grapple with today, most notably in the display of Confederate monuments, continued segregation of names listed on WWI soldiers’ memorials, the naming of university and government buildings, and battles over what is worthy of inclusion in our state’s history textbooks. This school of thought has served a major obstacle in our continuing struggle to build more inclusive historical and archival institutions. Study of this period is a reminder that the stories we tell about ourselves matter. Greater inclusiveness in the historical profession must be accompanied by diversification in what stories, documents, and buildings we deem worthy of collection and preservation. Doing so would allow us to tell a fuller, more complex history of our state which is a necessary element of any effort toward true racial reconciliation.