A blog post by Ramon Jackson, African American Heritage Coordinator

This week marks the 65th anniversary of the Brown vs. Board of Education decision, the landmark 1954 U.S. Supreme Court case where justices unanimously declared that racial segregation in America’s public schools is unconstitutional. Chief Justice Earl Warren declared, “We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” This decision marked the culmination of nearly thirty years of civil rights litigation performed by the NAACP’s Legal and Education Defense Fund, Inc. Throughout that time, the Legal and Education Defense Fund had the support of an expanding grassroots civil rights insurgency that operated, in part, from within its local NAACP branches. This case was important in the fight against educational inequality, but also against segregation in all aspects of American life.

African Americans in South Carolina played a pivotal role in this decades-long struggle to dismantle the legal and constitutional foundations of Jim Crow and white supremacy. By the early 1940s, the South Carolina NAACP State Conference had become indispensable partners in the national office’s campaign for educational equality. In some cases their efforts were unsuccessful like in the case of Charles Bailey, a Morehouse graduate, to sue for admission to the University of South Carolina Law School. In other cases their efforts were successful like the fight for the equalization of teacher salaries. Led by organizers like James Hinton, Modjeska Simkins, John H. McCray, and Osceola McKaine, the South Carolina NAACP State Conference also coordinated mass voter registration drives, organized political conventions, and filed lawsuits to end the “whites only” Democratic Party primary. The success of the State Conference inspired other African Americans to join the organization. Between 1946 and 1955, the number of local branches in South Carolina doubled from forty-nine to eighty-four. African Americans who resided in the state’s most rural, isolated, and powerless regions formed many of these new branches.

There were few places that fit this description better than Clarendon County, South Carolina. By 1947, black residents of this economically poor, politically repressive county emerged as key leaders of a grassroots campaign to improve educational facilities for local black children. Their efforts ultimately resulted in Briggs v. Elliott (1951), the first of five lawsuits that were later combined into Brown v. Board (1954). Clarendon County displayed a myriad of deficiencies in black education. In 1949-1950, the county spent $179 for each white child to attend twelve schools, while it spent $43 for each black child to attend an estimated sixty-one single and two-teacher schools scattered across the county. In addition to separate and inferior facilities, black children had to walk to school, sometimes many miles, while white children rode buses. The Briggs case began as a simple request to provide bus transportation to black children in Summerton.

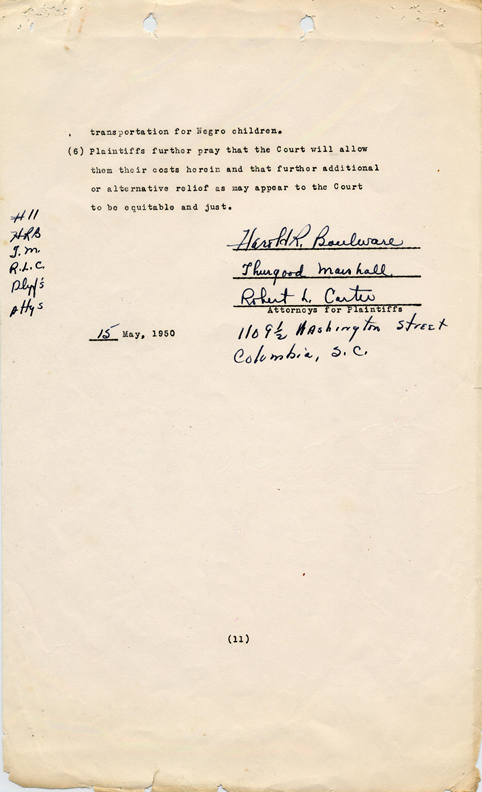

As early as 1943, the issue of adequate bus transportation became a subject of conversation between members of Clarendon’s black community, most notably Levi Pearson. Pearson, a sizeable landowner, and his elder sons regularly drove area children in the back of an old pickup truck to the nearby Mount Zion school. Three years later, Levi Pearson, his brother Hammett Pearson, and NAACP organizer Rev. Joseph A. DeLaine solicited funds from local parents and purchased an old school bus from the county. They made necessary repairs, purchased gas, hired a driver, and transported children to the Scott’s Branch School, where three of Pearson’s children attended. They continued to solicit funds from the local school board for operational expenses, but the board refused and bus services were eventually discontinued. In 1948, NAACP attorneys Thurgood Marshall and Harold Boulware filed a lawsuit on behalf of Levi Pearson. The case was dismissed before its opening session on June 9. Clarendon County officials had “discovered” that Pearson paid property taxes in School District No. 5, not in District No. 26. This left him without legal standing to sue in the district named in the lawsuit.

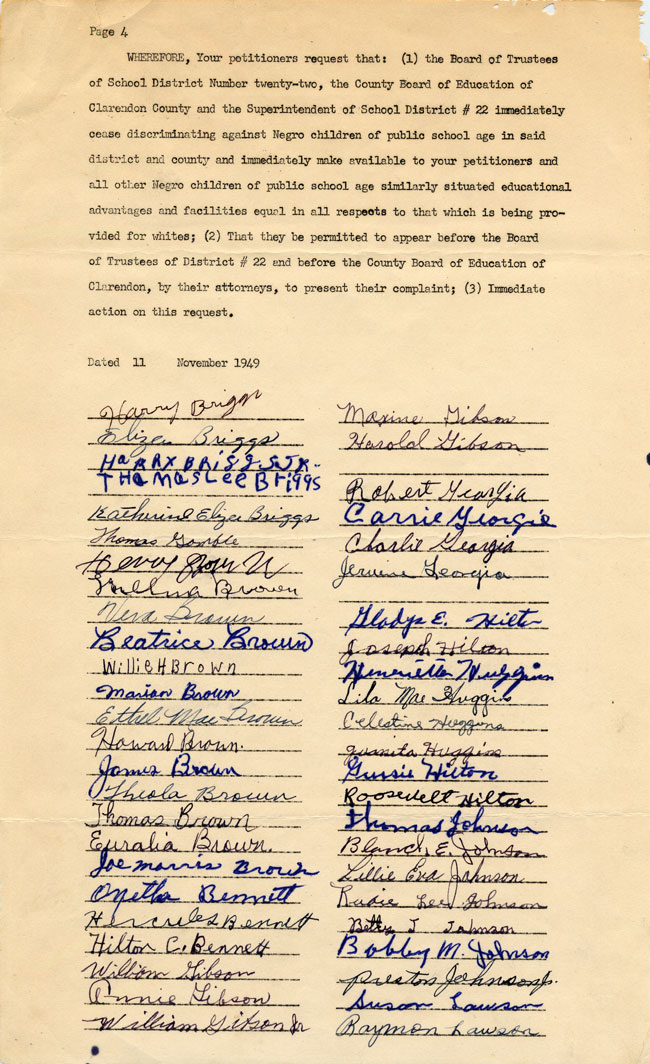

After a brief hiatus, Marshall and his legal staff met with state NAACP officials and representatives from Clarendon County. Marshall informed the gathering that the NAACP would only support a lawsuit to support equal educational opportunities and facilities for black children. Senior students and parents at Scott’s Branch had filed six petitions seeking such changes, but these attempts were ultimately unsuccessful. On November 11, 1949, the parents and students submitted a new petition demanding improvements. The list of 120 potential plaintiffs was narrowed to twenty adult petitioners, all from school District 22 in Summerton.

They lost the case in District Court, but it was eventually appealed to the United States Supreme Court, where it became part of the famous Brown case. Federal District Court Judge Waties Waring directed Marshall to amend the complaint to directly challenge the constitutionality of segregation. For Waring, legal segregation had become critical to the advancement of racial equality in South Carolina and, in his view, an imperative of the ongoing Cold War. “To me the situation is clear and important,” he wrote in what became his dissenting opinion in Briggs, “particularly at this time when our national leaders are called upon to show to the world that our democracy means what it says and that this is a true democracy and there is no undercover suppression of the rights of any citizens because of the pigmentation of their skins.”

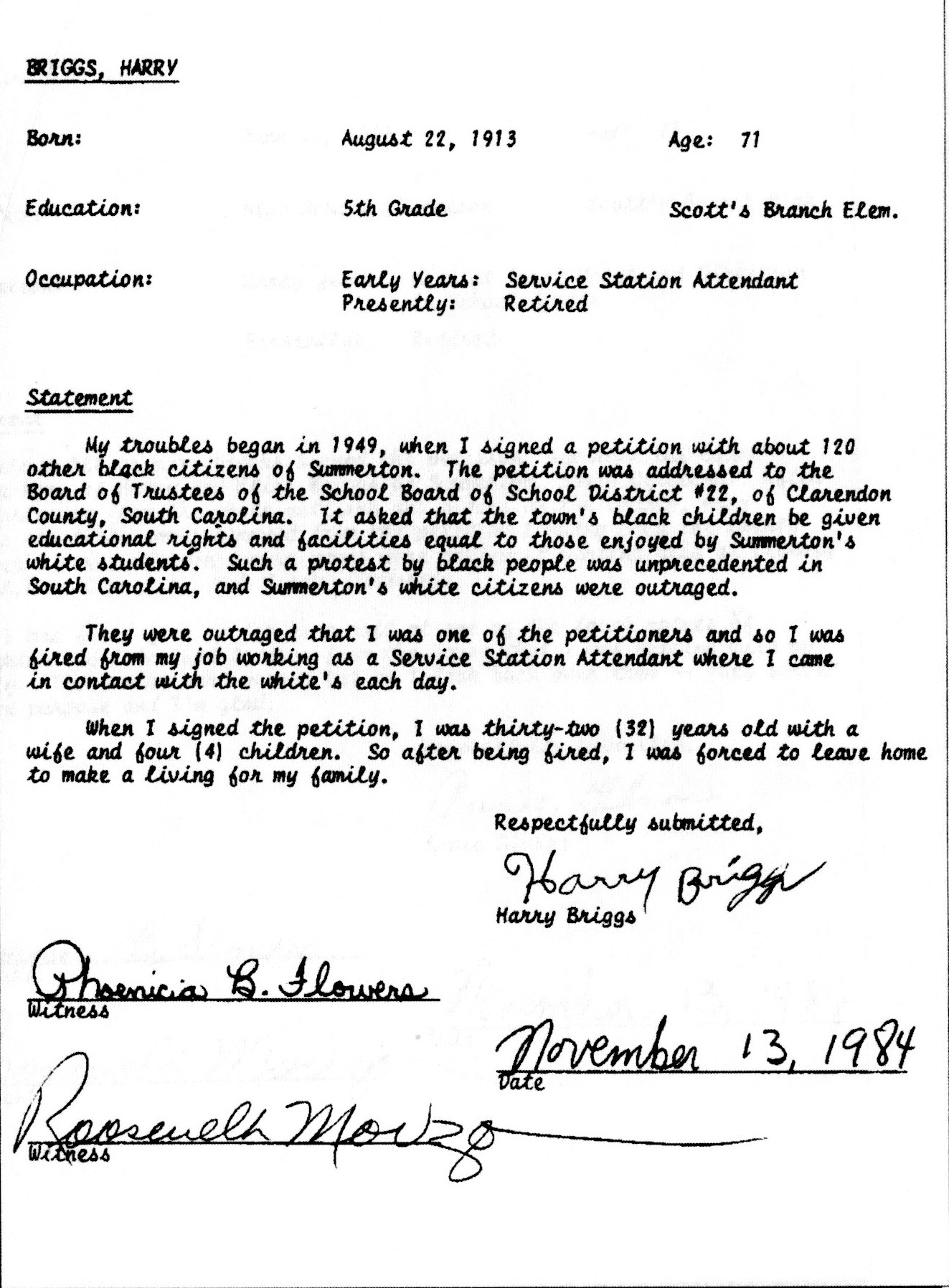

Almost all of the supporters of the movement faced retaliations from whites in Summerton. Harry Briggs, a service station attendant, and his wife Eliza, who worked as a maid, were both fired for signing the petition. Annie Gibson and Maize Solomon, who worked as maids at the Windsor motel, also lost their jobs. Rev. DeLaine, now the recognized leader of the Clarendon movement, had already been fired from his teaching and administrative duties at the Silver School a few months earlier. Because of threats and rumors of retaliation against him, the presiding elder of the South Carolina District, A.M.E. Church reassigned him to a pastorate in Lake City in April 1950. In October 1951, his home in Summerton was burned to the ground while local firemen watched. Several times in 1955 passing cars fired upon DeLaine’s home. He and his family eventually had to flee their home. His wife and children remained in South Carolina but DeLaine fled the state and never returned.

The inspiring yet tragic story of Rev. DeLaine, the Briggs family, and other petitioners has received considerable attention from historians in recent decades. However, it has yet to reach national prominence within America’s popular civil rights narrative. A simple explanation for this is that Brown, rather than Briggs, was immortalized among the five lawsuits due to a scheduling quirk or, more likely, Supreme Court justice Tom Clark’s suggestion that renaming the case would make it appear less like the court was singling out the South.

Another reason is that many of the schools, churches, residences, and other public spaces associated with the local NAACP movement in Clarendon County have either been demolished, neglected, or commemorated without acknowledging this important chapter in their history. It is not only important to remember this case for its contribution on the national level, but also the impacts felt in its aftermath in Clarendon County. The force of white economic sanctions, the threat of racial violence, and the loss of its key leaders devastated the Clarendon NAACP movement as a result of Briggs v. Elliot and later Brown v. Board. White resistance to school integration persisted and Clarendon County did not submit to a desegregation plan until 1965. White parents steadily withdrew their support from public schools, opting instead to send their children to private academies. The aftermath of Briggs v. Elliot had a long-lasting impact on black schools in Clarendon County and South Carolina.

As part of a growing effort to document and commemorate the story of Briggs v. Elliott and, more broadly, the civil rights struggle in South Carolina, the South Carolina African American Heritage Foundation (SCAAHF) and its partners have developed The Briggs v. Elliott Tour. The brochure map and walking tour of historic sites associated with Briggs is a product of the Summerton Community Action Group and the SCAAHF. It was published with the support of the town of Summerton and the Columbia SC 63 Civil Rights Project. The tour highlights the former site of the original Scott’s Branch School and Summerton High School, two educational institutions considered in the Briggs lawsuit. The trail also includes residences and churches that were central to the movement, such as the homes of Annie Gibson and the Briggs family, and Liberty Hill AME Church, a frequent site of meetings during the buildup to the lawsuit.

The brochure is the latest in a series of publications created by the SCAAHF to support the mission of the South Carolina African American Heritage Commission (SCAAHC), which identifies and promotes the preservation of historic sites, structures, buildings and culture of the African American experience in South Carolina. We hope to expand expand this tour to include relevant sites in other South Carolina cities such as the Modjeska Monteith Simkins House in Columbia, home to the civil rights organizer most responsible for raising funds and collecting supplies for those who suffered as a result of their courageous struggle for justice, or the former site of Motel Simbeth, an establishment run by Simkins whose original location was recently rediscovered.

By commemorating these sites with state historical markers, brochure maps, civil rights wayside tours, National Register nominations, and cultural tourism websites such as The Green Book of South Carolina, we pay homage to the everyday citizens that fought for educational equality, radical democracy, and civil rights in Clarendon County and other parts of South Carolina. These spaces serve as a reminder to the movement and individuals who made an important impact on South Carolina and the nation. Their preservation and interpretation can be used to remember the past while also analyzing how our past influences our present and future.