A Blog Post By Evan Spencer

The South Carolina Department of Archives and History preserves the records of South Carolina’s state and local governments, dating back to 1671. One of our primary functions is to help people access these records for historical, legal, or genealogical research. Researchers from around the world call, email, or visit our reference room to work on anything from their PhD dissertation to starting their family history.

Several months ago, we received a call from a documentary filmmaker who was working on background research for a film about Willie O’Ree. In 1958, O’Ree became the first black player in the National Hockey League when he took the ice for the Boston Bruins against the Montreal Canadiens. The documentary will focus on not only O’Ree’s story as the NHL’s first black player and his work to make hockey more inclusive, but also on his background and the legacy he carries on.

One of the threads the filmmaker found in her background research was one of O’Ree’s ancestors listed in a record called Carleton’s Book of Negroes, 1783. This book lists the names of about 3,000 formerly enslaved people who escaped during the American Revolution and joined the British Army under the promise of emancipation. Many of those people escaped from South Carolina during the British occupation of Charleston, beginning in 1780.

The filmmaker explained that the entry she found in the Book cited a young man named Paris who had escaped from a “Col. Oree” in Charlestown, South Carolina. She contacted us in the hopes that we could provide more information on Paris to help her tell Willie’s story.

Paris, 19, stout lad, (Cornet Merrell). Formerly the property of Col. Oree, Charlestown, South Carolina;

Left him 4 years ago & joined the British troops. GMC. (SCERA, Transcription of the Book of Negroes, Book 1, p77)

Researching Paris O’Ree

Researching formerly enslaved people in South Carolina is a difficult task, but not impossible. There are several different types of records that often list enslaved people by name: bills of sale; probate records like wills, estate files, inventories, and appraisements; deeds of gift; and our miscellaneous records are all good places to start. The unfortunate key to all of this is that since enslaved people were viewed as property, their names only appear in government records pertaining to the person who owned the enslaved. In this case, we had the name of Paris’s previous owner: “Col. Oree.” That may not seem like much, but it gave us enough to start our research to see if we could find out more about Paris.

Our first step was actually an assumption based on years of experience in South Carolina. The name “Oree” seemed to us to be a phonetic spelling of “Horry,” the name of a prominent family of South Carolina Huguenots (French Protestants). One key thing to remember when researching names in the past is that spelling was not standardized, as most people couldn’t read or write! So “Horry” becoming “Oree” when a British officer wrote down Paris’s entry in the Book is not surprising at all, given how South Carolinians pronounce Horry County even to this day!

Another angle that we explored was the fact that the Book referred to Paris’s previous owner as “Col.” Horry. From our Revolutionary War records, we came up with three potential Horrys that served as colonels at various points in their lives: Peter, Daniel, and Elias. This narrowed our search a bit, but it did not give us any answers about Paris.

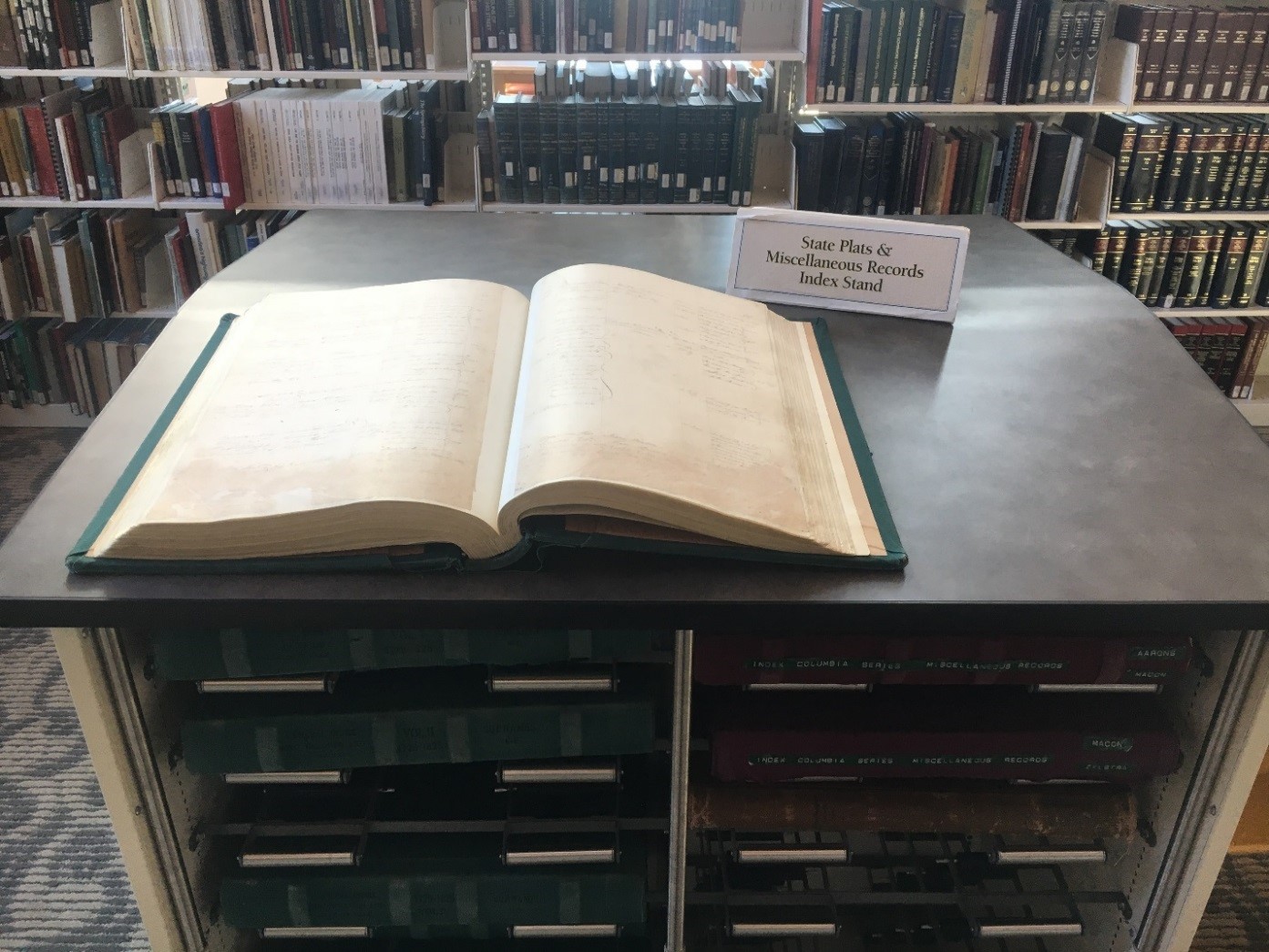

The next step in our research was to go to our Miscellaneous Records indexes. The Miscellaneous Records series (S213003) contains records of the Secretary of the Province (later called the Secretary of State) dealing with a wide array of legal duties carried out by the Secretary. These include bills of sale, deeds of gift, manumissions, marriage settlements, and guardianships, among many others. The records are all indexed in volumes here in our reference room, by the names of the people recording their documents with the Secretary.

With the information from the Book in hand, I had a perfect window to search in the Miscellaneous Records indexes. If Paris was 19 in 1783, he would have been born around 1764. He escaped in 1779-80, so I had a window of about 14 years to search for him in our documents. In the index, I found several potential entries to search pertaining to the three Horry colonels.

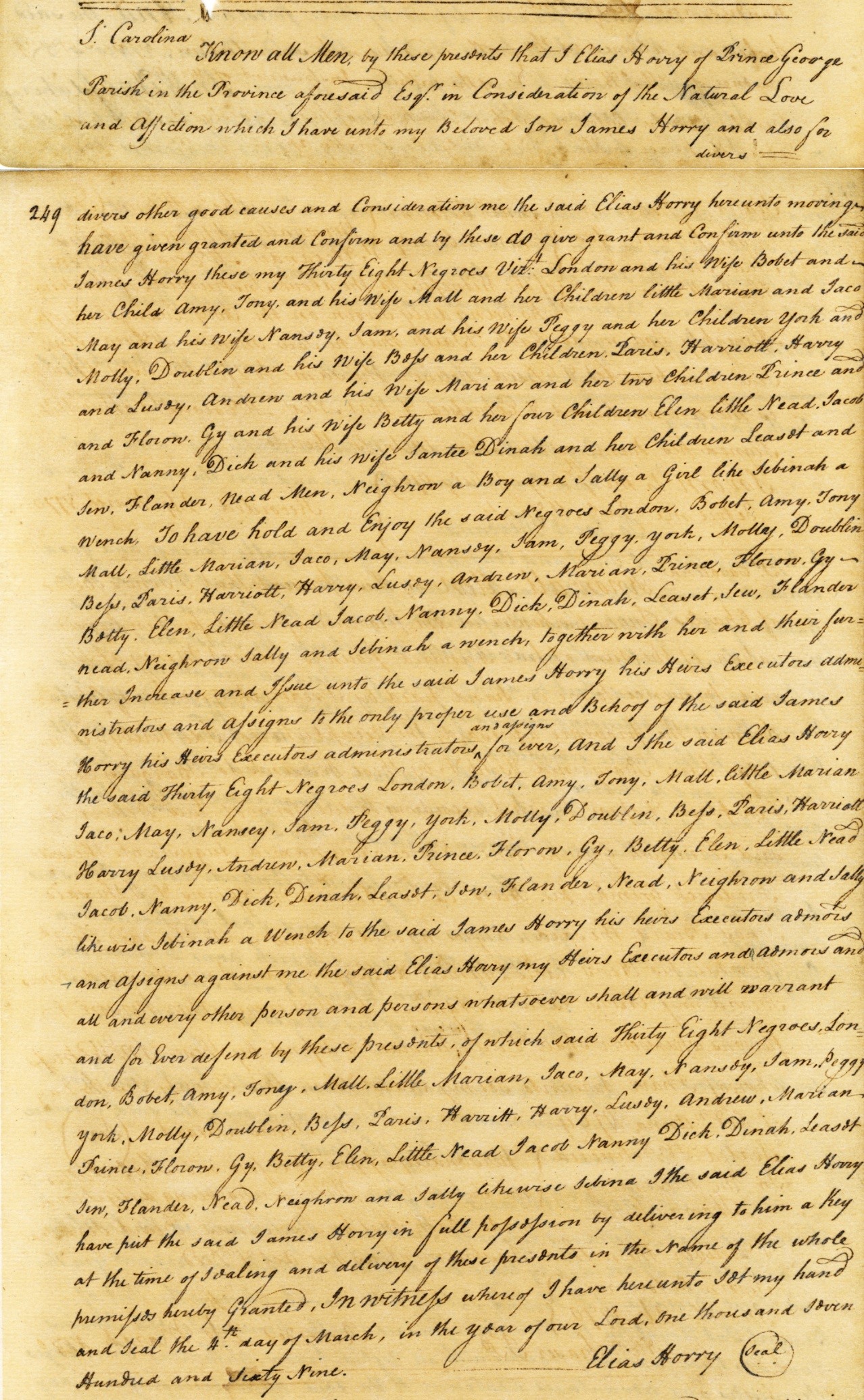

Of all the entries I found, the most promising were two deeds of gift from Elias Horry (whom we dubbed “Elias the elder” to avoid confusion). The index stated that these deeds were for “gift of 36 slaves to Thomas Horry” and “gift of 38 slaves to James Horry.” So I went to Miscellaneous Book OO to take a look at the deeds. The first entry listed the names of 36 enslaved people being transferred from Elias the elder to his son Thomas, but there was no one named Paris. The second entry was a deed of gift from Elias the elder to his son James in 1769. Elias gave James 38 enslaved people, including:

Doublin and his wife Bess and her children Paris, Harriott, Harry, and Lusey

This was an exciting find! What we have here is proof that an enslaved person named Paris belonged to an Horry prior to the Revolutionary War. Further, Paris is listed as a child here, with his family unit. Not only did we find the evidence we were searching for, but we now knew Paris’s father, mother, and siblings’ names!

While finding Paris on the deed of gift was exciting, it actually confused the narrative a bit, as James Horry does not appear in our Revolutionary War records at all. If James was not “Col. Oree,” the main question we needed to answer to tell the story of Paris was: what happened to James between 1769 and 1780? Our first guess was that he died prior to the Revolution. But in checking the usual suspects--Wills, Estate Papers, and Inventories--we found no record of James Horry’s estate being probated. However, we ended up finding proof in one of our published abstract books, St. James Santee, Plantation Parish (F 277 .C4 B75 1996 in the SCDAH reference room), which showed that James Horry died in June 1773.

Since there were no probate records for James’s estate, we were not sure if he had any direct heirs that would have inherited Paris. So we decided to search the wills and probate files for James’s immediate family: his father Elias the elder, and his brothers Thomas and Elias the younger. Each of these Horrys died after Paris had escaped, so we knew that we would not find a direct reference to him. What we hoped to find were clues to what happened to James’s estate.

Elias the younger’s will from 1785 provided evidence for what happened to James’s estate. In his will, Elias states that he was an “heir-at-law” to James. The phrase “heir-at-law” proves that James died without a wife or children, so members of his immediate family were next in line to inherit his property, including Paris and his family.

In Elias the elder’s will from 1783, we found what we consider to be the best evidence of what happened to Paris when James died. The names Doublin, Bess, Harry, Lusey, and Harriott--the names of each of Paris’s family members--appear in the will. Finally, in many of our records, Elias the elder is referred to as “Col. Horry.” This includes his Audited Account file, which refers to him as “Horry, Col. Elias Sr.”

Each of these pieces of information helped us paint a clearer image of Paris O’Ree. It appears from the records that Paris’s family transferred from Elias the elder to James in 1769. When James died in 1773, we believe that the family transferred back to Elias the elder. Six years later, Paris escaped from one of Col. Elias Horry’s plantations and made his way to Charleston to join the British.

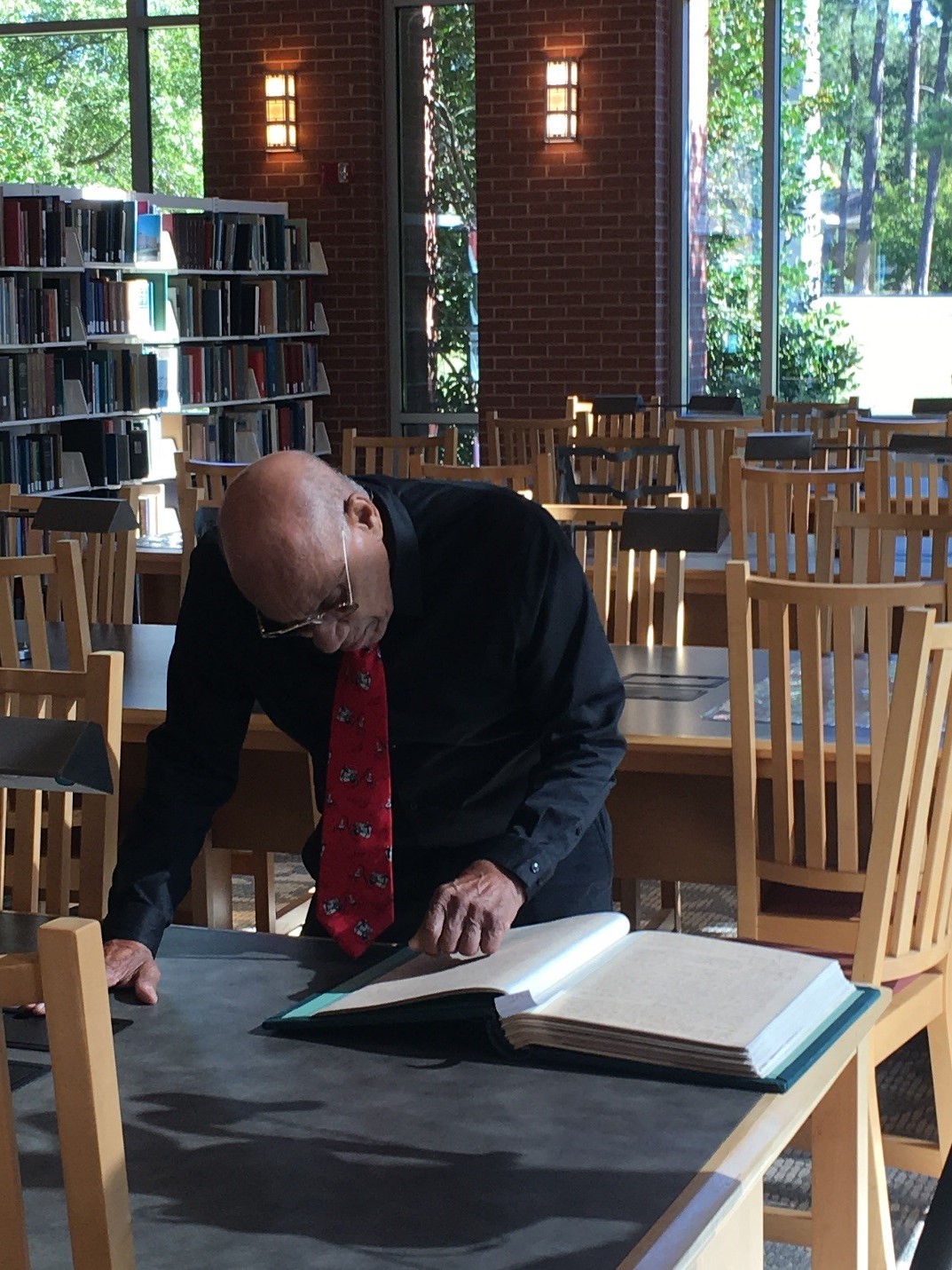

Hundreds of years and several generations later, Willie O’Ree stood in the reference room in the Archives, looking at the records that connect him to South Carolina, a state he had never been to in his previous 83 years. I explained the records and showed him a map of South Carolina and the general area where the Horry family lived (in St. James Santee and Prince George Parishes). When I showed him the deed of gift that included his ancestors’ names, Mr. O’Ree paused reflectively, and said “Harry was my father’s name.”

These records are a piece of Mr. O’Ree’s remarkable story. His ancestor, Paris O’Ree, escaped slavery at the age of 15 and claimed freedom. Some 178 years later, Willie O’Ree became the first black player in the National Hockey League. Two weeks after his visit to the Archives, Mr. O’Ree was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto, Canada.